EU-Moldova Summit in the Shadow of Union's Emerging Crisis in Eastward Enlargement

The first EU-Moldova summit, held on 4 July in Chişinău, had a primarily symbolic dimension in view of the EU’s inability to offer progress to this country on its path to membership. Hungary’s blocking of Ukraine’s European integration is also slowing down Moldova’s accession negotiations.

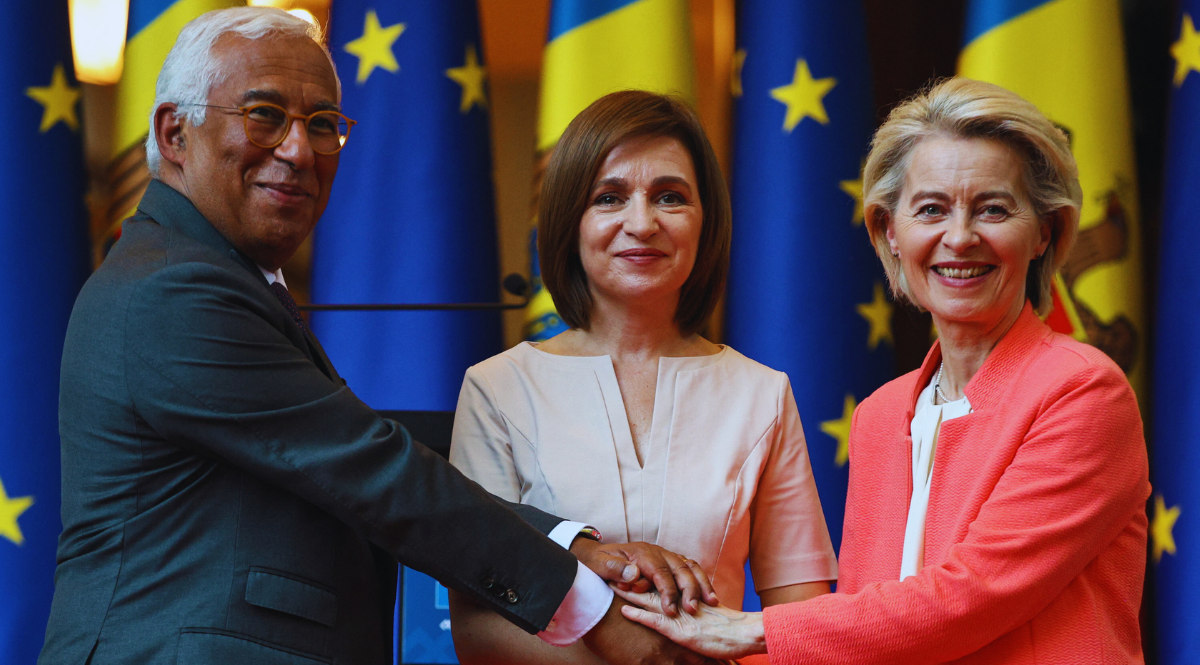

credit: Vladislav Culiomza / Reuters / Forum

credit: Vladislav Culiomza / Reuters / Forum

Why was an EU-Moldova summit held?

The summit served to demonstrate EU support for Moldova’s European integration and to maintain pro-EU sentiment in its society ahead of the parliamentary elections scheduled for 28 September. According to polls, the ruling Action and Solidarity Party, associated with President Maia Sandu, may lose its majority to pro-Russian groups. So far, EU summits of this kind in the context of enlargement policy have taken place with the two large partners—Ukraine and Turkey—and with a group of Western Balkan countries. The Union called the summit with Moldova in the face of the postponement of the decision to convene the first Accession Conference (formerly known as an Intergovernmental Conference, IGC) to open negotiations in specific areas. This is due to Hungary’s opposition to the opening of talks with Ukraine on the grounds that it allegedly violates the rights of the Hungarian minority, threatens to drag Hungary into war, and that accession would have a detrimental impact on the Hungarian and EU economies. Meanwhile, the EU is informally treating the candidacies of Ukraine and Moldova as a package.

What are the results of the Chişinău summit?

The summit—and holding it in Chişinău—was mainly symbolic. The presidents of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, and of the European Council, António Costa, in their final declaration reiterated their intention to open the accession clusters as soon as possible, meaning, to start the actual membership negotiations. They further declared their readiness to regularly organise EU-Moldova summits. They announced the disbursement of the first tranche (€270 million) of the €1.9 billion Growth Plan for Moldova, which is expected to help reform the country and revitalise its economy. They also confirmed previously agreed plans to include Moldova in the Single Euro Payments Area (SEPA) from October this year and to abolish EU roaming for Moldovan mobile network subscribers from 2026. They reiterated support for this country’s accession as an observer or associate partner of key EU agencies: EU Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA), European Medicines Agency (EMA), and European Environment Agency (EEA). They also declared their readiness to further support Moldova’s defence capabilities—it received €60 million from the European Peace Facility in 2025—and its resilience against hybrid threats from Russia.

At what stage is Moldova’s integration with the EU?

Moldova has been negotiating EU membership since June 2024 (it started together with Ukraine), but has not yet opened any cluster (there are six in the accession talks and they consist of 33 chapters in total). In early 2025, the EC expressed the hope that the first Accession Conference could take place in April and thus the first cluster on fundamentals would be opened, which includes the judiciary and fundamental rights (Chapter 23), freedom, justice and security (Chapter 24). Moldova applied for EU membership together with Georgia in March 2022, a few days after Ukraine did so shortly after the Russian invasion. It gained EU candidate status in June 2022 (along with Ukraine). The Dorin Recean government and President Sandu declared EU accession by 2030 as Moldova’s goal.

What are the reasons for the slowdown of EU enlargement to the East?

Both the candidate countries themselves and the EU have contributed to the slowdown of enlargement. On the one hand, reforms bringing the candidates closer to EU standards are slow, which is why Georgia gained candidate status a year and a half after Moldova and Ukraine, and also there are departures from democracy, which led to a de facto halt in EU talks with Georgia. On the other hand, the practice of blocking candidates by individual EU members is widespread. Moreover, if a blocked country is at the same stage of talks as another—as is the case for Moldova and Ukraine—then the EU states supporting enlargement face a difficult choice. It consists of whether to decouple the candidates on their path to the EU and succumb to pressure from the vetoing state, or to treat them as a package—contrary to the principle of gaining accession progress on the basis of individual merits—in a situation where delaying Moldova’s European integration carries the risk of political developments unfavourable to the process in the context of the autumn elections in that country. The reasons for the slowdown of EU enlargement to the East are therefore the same as in the Western Balkans, which was the only viable area for this policy until 2022 and where it has been in crisis for years.

.jpg)

.png)