U.S. Fosters Rwanda-Congo Peace Deal for Mineral Rights

On 27 June in Washington, the foreign ministers of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Rwanda signed a peace agreement, reached under U.S. auspices. It is based on a “security for minerals” formula. Although it carries the promise of development by linking the economies of the DRC, Rwanda, and the U.S. in the extractive sector, the chances of its full implementation are slim.

credit: Ken Cedeno / Reuters / Forum

credit: Ken Cedeno / Reuters / Forum

The genesis of the conflict between Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo is linked to the 1994 genocide of the Tutsis in Rwanda and the defeat of the Hutu militias, who then moved to the DRC where they still operate today under the name of the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR). Rwanda regards the militants’ presence there as a threat not only to its own security but also to Congolese Tutsis, and therefore fostered and cooperated with successive rebel groups composed of this ethnic group in eastern DRC. At the same time, while present there directly or through proxies, Rwanda acquired mineral resources from the region, rich in gold, copper, cobalt, tantalum, lithium, and others. Earlier this year, the newest of these pro-Rwandan groups, M23, supported by around 7,000 Rwandan troops, occupied two provincial capitals in eastern DRC, Goma and Bukavu, while the Congolese forces remained passive. It also mined and shipped about 120 tonnes of Congolese coltan (tantalum and niobium ore with wide use in electronics) to Rwanda every month. The Congolese state teetered on the brink of collapse while M23 and its political wing, the Congo River Alliance (AFC), appeared to be on the way to gradually occupying the entire country and installing their own government in Kinshasa. Then, the DRC leadership, taking the U.S.-Ukraine negotiations as an example, made an offer to the U.S. to grant broad access to mineral resources in exchange for help in ending the war.

Motivations of the U.S. Administration

The commitment to resolving the Rwanda-DRC conflict is part of a new U.S. approach to the continent based on “commercial diplomacy”, the framework of which was presented by Ambassador Troy Fitrell of the State Department’s Bureau of African Affairs at the U.S.-Africa Business Summit held a week earlier in Angola. He indicated that up to 300,000 U.S. companies could do business in Africa if the conditions were right, and that government institutions needed to be “more aggressive” in pursuing opportunities on the continent.

The leading exponent of this logic of U.S. action in Africa and the architect of the current agreement is Trump’s Africa advisor, Massad Boulos. He negotiated with Rwanda and the DRC, building on previous Angolan and Qatari initiatives, which had brought their positions closer together but failed to conclude the talks. From Boulos’ point of view, a key complement to the security agreements will be a separately negotiated business package that will give the U.S. facilitated access to valuable deposits. Equally important—and consistent with the current strategy—the agreement offers the chance to challenge China’s role as the dominant partner in the Congolese mining sector. The U.S. hopes its companies will replace the Chinese ones. Their presence would also increase the viability of the largest American infrastructure project in Africa for the export of minerals from the region, the so-called Lobito Corridor.

Terms of the Peace Agreement

On security, the agreement essentially implies the implementation of arrangements negotiated through Angola’s mediation in October 2024 (not implemented due to the two sides’ leaders’ unwillingness to compromise). These assume the neutralisation of the FDLR by the Congolese side and the withdrawal of Rwandan forces from the DRC. This is to take place within 90 days (previously, the DRC had demanded the immediate withdrawal of the Rwandans as a precondition for the talks). There is also to be a joint Congolese-Rwandan mechanism to monitor this within 30 days. The parties also pledged not to support armed groups threatening either of them in the future. In particular, this means a commitment by Rwanda to sever ties with the M23 rebels. Its support has been the main reason for the group’s military successes in recent months. The parties also pledged to support further direct talks between the DRC authorities and M23, which are taking place with Qatari mediation. This implicitly assumes that Rwanda, even if it formally dissociates itself from ties with the M23, will retain influence over the group, and that the success of these talks between the Congolese authorities and the rebels will largely depend on its attitude.

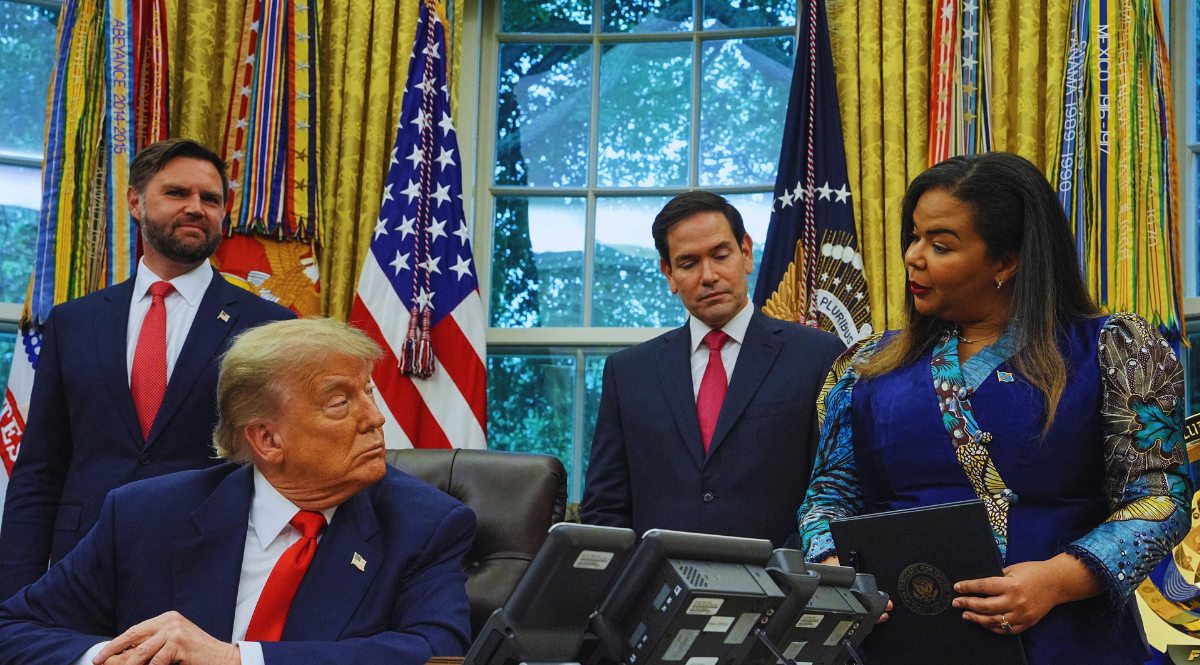

With regard to economic issues, the parties are to establish a framework for joint management of mineral resources and the integration of supply chains between Rwanda and the DRC within three months. This is to enable U.S. businesses to invest and trade in critical minerals. A detailed plan for a broad U.S. economic entry into the region is yet to be worked out in a separate agreement (unofficially, there is talk of taking over mining licences or control of a deep-sea port, among other things). Trump, when receiving the heads of the Rwandan and Congolese foreign ministries in the Oval Office after initialling the agreement, announced that the presidents of the two countries are expected to sign it in Washington this summer. However, criticism is already mounting of the “neo-colonial” logic of the DRC agreement under which the eastern part of the country, rich in minerals, would be placed under the economic “protectorate” of the U.S. Among other critics, Congolese Nobel Peace Prize winner Dr. Denis Mukwege points out that violating the country’s sovereignty in this way is unconstitutional.

Opportunities and Threats

The signing of the agreement does not yet mean peace. Only sound implementation of it by the parties—Trump threatened them with severe penalties “financial and otherwise” if they violate it—offers a chance to calm the situation. For this, however, a rebuilding of trust and political will between the parties will be needed. At this stage, there is no breakthrough in this regard.

The neutralisation of the FDLR militia appears to be a done deal. This will deprive Rwanda of the most significant justification of its direct and indirect intervention in the DRC. The agreement thus offers a chance to reduce the intensity of the conflict, which has led to the forced displacement of about 4 million people since the beginning of the year, mainly within the Congolese provinces of North Kivu and South Kivu. This opens up the prospect of at least some of them returning home.

Another problem is the lack of inclusivity and the fragmented nature of the agreement. While it was signed by representatives of the two states, missing from the negotiating table were their “non-state” armed allies (proxies), who may not necessarily feel bound by the commitments made between the capitals. M23 representatives have already conveyed that the agreement will not be binding on them. This was in response to a caveat put forward by the signatory to the agreement from the Congolese side, Foreign Minister Thérèse Kayikwamba Wagner, who stressed that the first test of the agreement would be for the Congolese state to regain full control of its territory. Likewise, it may be difficult to force compliance with the agreement from the group Wazalendo (“patriots”), the strongest pro-government Congolese guerrilla formation, which, faced with the weakness of the state, was the only one to take up arms against M23 and force its withdrawal from certain areas. It seems wishful thinking to point to UN forces (MONUSCO) as key security partners, given that this mission is completing its mandate and is withdrawing from the DRC.

The attempt to “hand wave” economic conditions into reality may prove problematic. U.S. companies that have in the past undertaken investments in the eastern DRC have over time abandoned them because of the risks and difficulties they encountered, and the U.S. authorities’ incentives can hardly be expected to make them consider local conditions more favourable.

.png)