Moldova and Separatist Transnistria Facing Severe Energy Crisis

(1).png) Amos Chapple / Zuma Press / Forum

Amos Chapple / Zuma Press / Forum

Transnistria Crisis

The supply of free gas from Russia was a form of subsidy for Transnistria. Gazprom did not demand payment but accrued debt, about $11.1 billion. The 2 billion m3 (bcm) of gas received annually (about 5.7 mcm per day) was sold by the authorities to the population and companies at discounted rates, of which 1.8 bcm was sold to the three largest factories: the steel mill and cement plant in Rybnitsa and the MGRES power plant, both of which exported mainly to the EU and Moldova. This money funded the breakaway region’s budget by about $500-700 million a year.

Transnistria now is threatened by a humanitarian crisis. Faced with the prospect of an end of Russian gas transit through Ukraine, its authorities declared a state of emergency in the energy sector on 10 December 2024. Gas already in pipelines is reserved only for cooking, but there is only enough till the end of January. MGRES will operate on an emergency basis for about 52 days thanks to coal stocks and five-hour-a-day power cuts. Homes have been cut off from central heating—most of the region’s 300,000 residents live in blocks of flats connected to gas-fired heating plants—as have schools and kindergartens. Energy-intensive companies, excluding the food industry, have halted operations. By 10 January, Transnistria’s industrial production had fallen by 50% compared to this time a year ago. Imports have fallen by 43% and exports by 60% ($7 million and $3.3 million, respectively).

Moldova’s Energy Problems

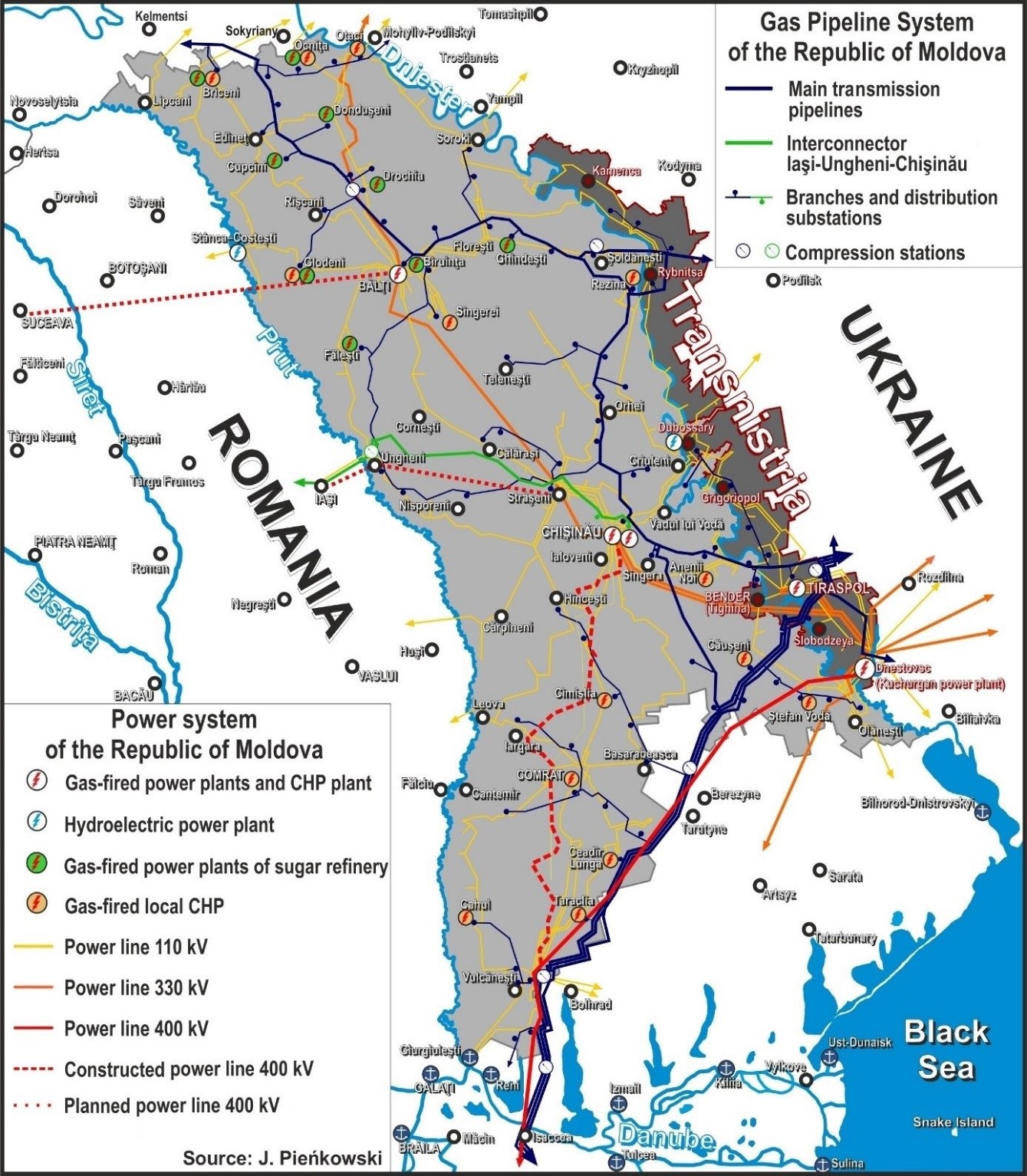

A state of emergency in the energy sector was announced in Moldova on 16 December. It allows the government to mobilise additional funds for the purchase of fuel through simplified procedures and price subsidies. Electricity tariffs have almost doubled since 1 January, as supplies have been completely cut off from MGRES, which provided up to 80% of Moldova’s electricity, while its own production provided up to around 35%. The power deficit is being covered by purchases from Romania. Ukraine generally has no surplus due to war damage. Imports are further hampered by the lack of a developed cross-border network—the 400 kV Vulcăneşti-Chişinău line is to be completed only by the end of this year, while construction of the Suceava-Bălţi line is to begin.

An additional challenge for Moldova is the high price of power imports from Romania. Out of a shortfall of about 600 MW at the peak, only about 300 MW can be bought under contracts that cost about €110 per MWh, compared to €63 from MGRES. The rest is purchased on the energy exchange, costing up to €300 per MWh during peak hours. To alleviate the price pressure, on 9 January, Moldova, with the support of the Romanian government, contracted a further 30 MW at an undisclosed price from OMV Romania. The authorities in Bucharest have tried unsuccessfully to increase the volume of cheaper energy for Moldova. They requested the suspension of CO2 fees for Romanian coal-fired power plants, which would have halved the price, however, the European Commission refused, not wanting to set a precedent in the Emissions Trading System (ETS), but announced it would support Moldova with purchases.

In Moldova, the problems with high priced electricity overlap with a rise in gas prices of around 30% since December last year. However, this is not the result of Gazprom’s actions because Moldovagaz, the Moldovan national operator, has not bought Russian fuel since 2022. However, according to a contract in force until November 2026, Russia was transferring gas to Transnistria through Moldovagaz. The energy ministry, relying on miscalculations, did not order sufficient stocks in spring when fuel is cheapest on the exchanges.

Russia’s Objectives

Gazprom is obliged to supply fuel up to the Ukrainian-Moldovan border and Moldovagaz to transfer it to Transnistria. So, it is blaming the Moldovan authorities for cutting off gas to the region and the resulting increases in electricity prices in Moldova, citing an alleged debt of Moldovagaz of up to $709 million. The Dorin Recean government refuses to pay it, referring to an international audit according to which the debt is $8.7 million.

Russia accuses Moldova of sparking a humanitarian catastrophe to force the reintegration of Transnistria and promises to defend its “own citizens and compatriots”. However, Russia prefers to avoid a complete collapse of the region, which could shake its inhabitants’ confidence in Russian patronage and prompt them to seek help from the Moldovan authorities. That is why it assured Vadim Krasnoselsky, the separatist president of Transnistria, during his visit to Moscow in mid-January that it would deliver gas “soon” as humanitarian aid, presumably without producing electricity for Moldova. On his return, Krasnoselsky announced Transnistria’s willingness to pay for the gas (likely with Russian credit) and called on the Moldovan government to deliver it, but at the same time presented additional, impossible demands. He is certainly doing this in tandem with Russia to try to limit Moldova to a passive intermediary transferring Transnistria gas delivered by a supplier designated by Gazprom.

Moldova’s Remedial Action

The Recean government is seeking to defuse the crisis, citing the need to protect its citizens in Transnistria. In a bid to avoid the crisis, as recently as last November, Energy Minister Victor Parlicov unsuccessfully negotiated with Gazprom in Saint Petersburg during the first visit at this level in Russia since February 2022. He was hoping to supply the region by an alternative route via Turkey and a reverse flow on the Trans-Balkan Pipeline. Moldova offered Transnistria humanitarian assistance and help to purchase gas on EU markets and a loan of 3 mcm of emergency fuel to maintain pressure in the pipelines. The EU has also offered its support to Transnistria, including €30 million to buy gas for the first 10 days of February, from which MGRES would also resume electricity production for Moldova.

Faced with the crisis, the Recean government has strengthened its information policy. It appeals to the patriotism of Moldovans and points to Russia’s culpability for the price increase, while avoiding the issue of Ukraine’s blocking gas transit. However, there is no coherent message to reinforce the loyalty of Transnistrians to the authorities in Chişinău. The pro-Russian opposition in Moldova blames the crisis on President Maia Sandu and the PAS government, whom it accuses of Russophobia and pushing for conflict with Russia. The opposition’s favourite candidate, the fugitive oligarch Ilan Şor, is boosting the popularity of his Şor Party by paying the inhabitants of the autonomous Gagauzia it rules, as well as the towns of Orhei and Taraclia, with allowances, allegedly from his own fortune.

Conclusions

The energy crisis in Transnistria is a consequence of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which has refused to further cooperate with the aggressor on gas transit. Being cut off from virtually free supplies has led to the collapse of the region’s economy and threatens its inhabitants with humanitarian catastrophe. Despite this, Russia is trying to place the blame on Moldova, although the latter is seeking to alleviate the crisis by offering to help Transnistria purchase fuel from other sources. Most likely to retain its influence in the region, Russia will seek to resume gas supplies. In this context, it may allow the region to accept Moldova’s and the EU’s offers of assistance, but will present them as its own diplomatic success and part of the announced Russian humanitarian aid.

Moldova became independent of Russian gas in 2022 and buys it on EU markets, so its gas supply has not been directly affected by the end of transit through Ukraine. However, it remained dependent on electricity purchased at below-cost prices from Transnistrian MGRES, which, with the cessation of free Russian gas supplies, stopped production for Moldova’s needs. The consequences of this are soaring energy prices, which will intensify public disillusionment with the government of President Sandu and PAS. As a result, the party may lose its majority in the parliamentary elections in the middle of this year to pro-Russian parties that are promising to resume energy cooperation with Russia.

Poland has consistently supported Moldova’s aspirations for EU membership. It is in Poland’s interest to strengthen Moldova’s energy security by linking it more closely to European markets. Poland’s presidency of the Council of the EU could seek additional ad hoc financial support for Moldova—especially with Romania and the Baltic and Nordic states particularly favourable to it—in the purchase of electricity and price subsidies for residents. This would alleviate the price pressures and serve to stem the rise in pro-Russian sentiment.

.png)