Appointment of Andrej Babiš's Third Government in Czechia

The swearing-in of the government on 15 December last year and the vote of confidence on 15 January this year mark the return of Andrej Babiš to power after four years. The creation of a government by ANO with the far-right Freedom and Direct Democracy (SPD) and the Eurosceptic and anti-environmental Motorists for Themselves (AUTO) has brought about changes in Czech foreign policy. Babiš's cabinet is strengthening its critical stance towards EU policies, limiting support for Ukraine and intensifying cooperation with Slovakia and Hungary.

Eva Korinkova / Reuters / Forum

Eva Korinkova / Reuters / Forum

New Coalition, Old Prime Minister

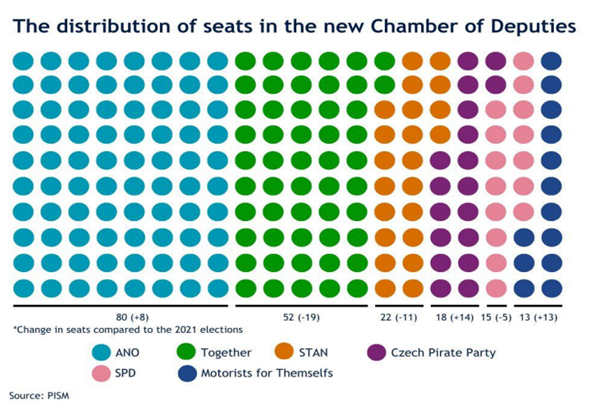

Babiš's cabinet replaced Petr Fiala's government, which resigned on 6 November last year after ANO’s victory in the October parliamentary elections. The SPD and AUTO were its only partners in coalition talks due to the intense conflict with the parties that made up Fiala's outgoing cabinet. With 108 out of 200 seats in the Chamber of Deputies, the new coalition secured a vote of confidence for the government in January.

Prime Minister Babiš has taken up this position for the third time. He previously held this office twice between 2017 and 2021 and is the first Czech head of government to return to this position after a break. He owes his victory in the recent parliamentary elections to a campaign focused on anti-immigration, social (abandoning the gradual increase in the retirement age) and economic (lowering electricity prices) issues.

ANO's strong position in the current term of the lower house of parliament (80 seats) allowed it to take over eight ministries, in addition to the position of prime minister, compared to four for AUTO and three for SPD. At the same time, it gained the greatest influence over the ministries responsible for the economic situation: the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Industry and Trade. Prime Minister Babiš appointed his closest associates, Alena Schillerová and Karel Havlíček, as deputy prime ministers. ANO also took over the Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of the Interior, among others. On behalf of the SPD, retired General Jaromír Zůna became Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Defence. In addition, the leader of this party, Tomio Okamura, took the position of Chairman of the Chamber of Deputies. The Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs is the leader of AUTO Petr Macinka. He is also temporarily in charge of the Ministry of the Environment, which is especially important for AUTO, given the anti-environmental profile of this party.

The President’s Role in Appointing the Government

Despite his limited constitutional powers, President Petr Pavel had an influence on the shape of the government. He announced that he would block the appointment of politicians with anti-EU and anti-NATO views – characteristic of the SPD – to ministerial posts (following his predecessors’ example). By delegating non-partisan experts to the government, the SPD avoided having its nominations rejected. Moreover, Pavel managed to block the appointment of AUTO’s honorary chairman Filip Turek–who, among other things, has spread racist and xenophobic content on social media–first to the post of foreign minister and then to that of environment minister.

President Pavel made Babiš’s appointment as Prime Minister conditional on the resolution of his business and political conflicts of interest. As a result, Babiš announced that he would transfer his shares of the Agrofert holding company to a trust fund to be established and managed by an independent administrator. Only after this public statement was he sworn in as Prime Minister.

Shifts in Czech Foreign Policy

Both the entry into the government of the SPD, which advocates normalisation of relations with Russia and confrontation with Ukraine, and the Babiš cabinet's departure from promoting values in international relations, mark a break with the Eastern and security policy of the Fiala government. Although the previous Babiš cabinet – in response to the sabotage in Vrbětice – announced the expulsion of a record number of Russian diplomats in 2021, the current government represents a conciliatory stance towards Russia, hoping that it will cease its military operations. Therefore, the government's programme does not condemn them, but only mentions supporting diplomatic steps leading to the war’s end.

The consequence of Czechia signalling its favour towards Russia is the announcement of a reduction in aid to Ukraine. Babiš is using the American administration's attempts to end the war and the declared need to reduce its own budgetary expenditure as a pretext for this. Therefore, Czechia will no longer financially support the ammunition initiative it initiated, although its Prime Minister has announced that it will remain its coordinator. In turn, SPD leader Okamura, in his New Year's speech, accused the Ukrainian authorities of, among other things, corruption and a penchant for luxury, while failing to notice such phenomena in Russia, which has led to diplomatic friction with Ukraine.

Although Babiš presents himself as politically willing to support Ukraine, emphasising a different approach from that taken by Slovakia and Hungary, the actions of the new government cast doubt on this. Though unlike the leaders of both countries, he emphasised this difference by signing the conclusions of the December European Council summit, at the same time, Czechia joined the group of EU countries blocking the decision to support Ukraine with frozen Russian assets. Furthermore, together with Hungary and Slovakia, it did not support the European Council's decision to grant Ukraine a €90 billion loan.

Despite the Eurosceptic composition of the coalition, Babiš’s talks with, among others, the presidents of the European Council and the European Commission were intended to demonstrate the government's readiness for constructive cooperation within the EU. Babiš signalled, among other things, his intention to increase Czechia’s involvement in the Security Action for Europe (SAFE) instrument. At the same time, he is critical of the EU's ETS2 emissions trading system, which the government rejected, together with the EU migration pact, at its first meeting on 16 December last year.

The new government is enthusiastic about both the Visegrad Group and building bilateral relations with Slovakia and Hungary as members. This is why, during his visit to Bratislava – in accordance with the tradition of the first official foreign trip, Babiš announced the resumption of Czech-Slovak intergovernmental consultations, which had been suspended by Fiala's government after the return to a pro-Russian policy by Robert Fico's government in Slovakia, appointed at the end of 2023. This may result in attempts to restore intergovernmental cooperation within the V4, e.g. on migration or energy issues. Babiš’s raising of the issue of Visegrad cooperation in a telephone conversation with US President Donald Trump on 26 December last year may indicate a desire to also revitalise the V4 in the transatlantic sphere. Despite the crisis in functioning of this format, membership in it also served to emphasise Czechia’s important role in relations with the US.

Conclusions and Prospects

As the leader of the most moderate of the three coalition parties, Babiš will try to restrain the radicalism of his partners. These efforts will be hampered by Okamura's independent position as the Speaker of the Chamber of Deputies – the third most important person in the state under the constitution. Paradoxically, despite the political differences between the prime minister and the president (Babiš was Pavel's main opponent in the 2023 presidential election), Pavel will try to balance the anti-EU and anti-Ukrainian rhetoric of coalition politicians, mainly the SPD, which would be beneficial to the Prime Minister. It is likely that he will express pro-Western opinions and be critical towards Russia more often in order to protect Czechia’s image in the EU. Such differences in the positions of the most important people in the country mean a reduction in the coherence of Czech politics.

Babiš will most likely increase his influence in foreign policy at the expense of the foreign minister. This process is facilitated by Macinka's limited international experience and the resignation of Babiš's cabinet from the post of Minister for European Affairs. According to Babiš's plan, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs will focus more on economic diplomacy, which is similar to the models in Slovakia and Hungary.

The change of Czechia’s government is unfavourable from Poland's perspective, mainly due to the country's departure from its policy of comprehensive support for Ukraine, having previously been at the forefront of such efforts. At the same time, its pro-Russian stance will not be as ostentatious as Hungary's approach. In turn, the Polish authorities' position on Eastern and security policy, which differs from that of their Visegrad partners, limits the chances of reviving political cooperation within the V4 as proposed by Babiš. The cooperation between the prime ministers of Czechia, Slovakia and Hungary at the December European Council summit demonstrated the coordination of the EU positions of Poland's Visegrad partners without its participation. Nevertheless, Poland remains an important partner for Czechia on EU issues, particularly those concerning migration and the ETS2 system.